Almost any camera will focus on well-lit still subjects with the kit lens, so the casual photographer doesn’t need to worry about it. Focusing becomes a challenge when tracking moving subjects (such as sports and wildlife), when shooting in low-light, and when working with shallow depth-of-field. Telephoto lenses and fast lenses (with f/stop numbers such as f/1.8) have a shallow depth-of-field, which means the eyes of your subject can be in focus, but the background will be very blurry. For more information about depth-of-field, refer to Chapter 4 of Stunning Digital Photography.

Mirrorless vs. DSLR

Generally, DSLRs autofocus better than mirrorless cameras (when using the viewfinder). In fact, in our testing, the least expensive DSLRs were better at autofocusing on moving subjects than the most expensive mirrorless cameras, including cameras such as the Sony a6000 and Fujifilm X-T1 that advertise phase-detect focusing. This difference in focusing speed means a low-end mirrorless camera won’t be useful for candid portraits, sports, or moving animals. If you’re interested in those types of photography, check out DSLRs instead. Note that mirrorless cameras support both single shot and continuous autofocus modes. However, focusing tends to be so slow that continuous autofocus on moving subjects doesn’t work very well. In practice, you’ll generally get better results with single shot autofocus.

Different Focusing Technologies

Most modern DSLRs and many higher-end mirrorless cameras feature two different focusing mechanisms:

- Phase detection. The quickest way to autofocus, phase detection uses a pair of sensors for each focusing point. With a DSLR, light travels through your DSLR’s partially translucent mirror. Behind that mirror, at the exact same distance from the lens as your camera’s sensors, are one or more pairs of focusing sensors for each focus point on your camera. Those sensors see a small part of your picture from two slightly different angles. When the view from the two sensors lines up, that part of the picture is in focus and your camera can stop the autofocus process.

- Contrast detection. Contrast detection autofocus is much slower than phase detection autofocus; however, contrast detection is more flexible because it can focus on any part of the picture, not just where a focusing point exists. DSLRs can use contrast detection in live view mode and some support contrast detection autofocus while recording video. Contrast detection examines data from the camera’s sensor while adjusting the lens’ focus, and by comparing subsequent frames captured from the sensor, can determine whether a focus movement causes the captured image to get more contrasty (indicating more focused) or less contrasty (indicating less focused) at any point on the frame. Therefore, with contrast detection, a focus point can be anywhere in the frame. Most DSLR sensors only provide data at 30 frames per second or 60 frames per second, limiting how quickly the camera can capture subsequent views of the scene while focusing, and thus the overall focusing speed. Therefore, mirrorless cameras tend to have much faster contrast detection autofocus than DSLRs.

DSLRs, and some mirrorless cameras, focus primarily using phase detection autofocus. With a DSLR, any time you’re looking through an optical viewfinder, you’re using phase detection autofocus. All modern digital cameras also support contrast detection autofocus. If you’re looking at the live view display on the back of a DSLR, that means the camera’s sensor is receiving all the light from the scene and the camera has moved the mirrors out of the way. Without the mirrors, your camera can’t redirect light to the phase detection autofocus sensor. Therefore, it must use the slower contrast detection autofocus instead. The Canon 70D is one exception to this. Its dual-pixel AF technology provides phase detection autofocus in live view, greatly improving focusing speed when the mirror is up—such as when you’re recording video. Here’s a minor technical point about Sony Alpha cameras with Single-Lens Translucent (SLT) mirrors: their mirrors don’t move out of the way like those of a traditional DSLR. Whereas a DSLR uses the mirror to reflect light to both the optical viewfinder and the phase detection focusing sensors, on a Sony SLT camera, the mirror only reflects light to the focusing sensors; most of the light passes through the mirror to the sensor. This allows the SLT cameras to take advantage of phase detection autofocus at all times, even when taking pictures or recording videos. While those are huge benefits, I still recommend most people choose traditional DSLRs with optical viewfinders. That’s more technical detail than you need to remember, so here are a few key points:

- Phase detection is generally much better than contrast detection, especially for moving subjects.

- DSLRs support phase detection autofocus when you’re looking through the optical viewfinder.

- All digital cameras support contrast detection. DSLRs use contrast detection when you’re viewing the live view display.

- Phase detection autofocus is limited to specific focusing points, while contrast detection allows you to focus anywhere in the frame.

- Mirrorless cameras that advertise phase detection autofocus only support it when lenses designed for phase detection are used. Currently, very few lenses support phase detection. For example, the Olympus E-M1 supports phase detection autofocus, but not a single native lens is designed for that. The Sony a5100, Sony a6000, and Fujifilm X-T1 all support phase detection autofocus, but only a small handful of lenses are compatible with the system.

How Phase Detect Focusing Works

With most modern lenses, the focusing motor (which physically turns the lens elements to change the focus) is built into the lens. Every other part of the focusing is controlled by the camera body. All DSLRs, and some high-end mirrorless cameras, use phase detect focusing. When you focus your camera, it looks at the image coming through the lens and then tries to focus a little closer or farther away. Just like you have two eyes in your head, each focusing point in your camera is two separate sensors. When the focus is correct, the image from those two sensors lines up. At that point, the camera stops focusing. Of course, that’s an oversimplified explanation of a really complicated process. Focusing speed and precision are extremely important to portrait, wildlife, and sports photographers, so camera makers do everything they can to make the process as fast as possible. Unless you become a serious sports or wildlife photographer, you really don’t need to understand all the nitty-gritty about how different camera bodies autofocus. However, keep reading if you’re interested or you just want to understand the lingo. Every camera body has multiple focus points. There’s always one focus point in the center of the image and several others spread around the frame. Using the focus-and-recompose technique (described in Chapter 4 of Stunning Digital Photography), you only really need the center focusing point. However, the other focus points are useful for action shots where you don’t have time to focus and recompose. Not all focus points on a camera are created equal. Typically, the center focus point is the fastest, and the farther you get from the center, the less powerful the focus points are. Common types of focusing points include:

- Vertical. Vertical focus points detect contrast by looking up and down an image. Therefore, a vertical focus point would be able to focus very quickly on a shirt with horizontal stripes, but it might not be able to focus at all on vertical stripes.

- Horizontal. Horizontal focus points detect contrast by looking left and right through an image. They’re good at detecting vertical stripes (or any type of vertical contrast), but not great at focusing on horizontal subjects.

- Cross-type. These use both vertical and horizontal contrast detection. They can focus on just about anything, as long as the subject is well lit and isn’t a solid color.

It’s common for the center focusing point to be cross-type, and focusing points towards the edges of the frame to be horizontal or vertical. However, some cameras, such as the Canon 7D and 70D, use only cross-type sensors. Sometimes, a focusing point’s capabilities depend upon the minimum f/stop number of the lens you’re using. For example, the center focusing point might be cross-type with f/2.8 lenses, but only horizontal with lenses of f/4 or higher. There’s no practical application for this knowledge; it’s not likely to be a significant enough factor to justify spending hundreds or thousands on a different body or faster lens. In practice, you’ll use the camera and lenses you have and do the best you can with the focusing it provides. Most camera bodies support autofocusing when the lens’ minimum f/stop number is f/5.6 or lower. However, some Canon bodies (specifically, the Nikon D4S, Nikon D810, Canon 1DX, and Canon 5D Mark III) support focusing with f/8 lenses on some of their focusing points. This capability is important to wildlife photographers who often use teleconverters to extend the reach of their telephoto lenses because teleconverters also increase the lens’ minimum f/stop number.

Focus Point Positioning

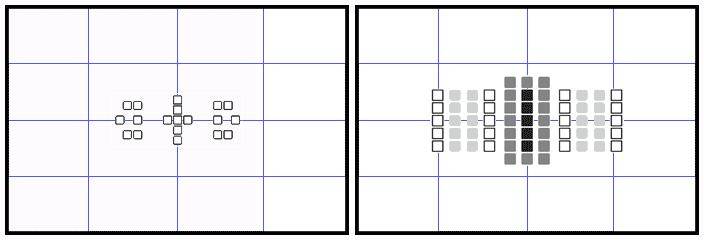

DSLR manufacturers often advertise the number of focusing points a camera offers, but the number of focusing points is not nearly as important as how they’re positioned in the frame. For example, some cameras have all their focusing points clustered in the middle of the frame, which is only useful if the subject will be centered in the frame. If you use the rule of thirds, as described in Chapter 2 of Stunning Digital Photography, you’ll want your focusing points to be 1/3 of the way through the frame. Only higher-end DSLRs provide that. Therefore, don’t consider a camera with a large number of focus points to be automatically superior to another camera. Instead, pick the camera with the focusing points closer to the edge of the frame. For example, the Sony Alpha a99 ($2,800) brags about having 102 autofocus points. This is mostly marketing fluff, because it has only 19 autofocus points that will allow you to attain initial focus. The remaining 83 points are only useful for continuing to track moving subjects after you initially focus, and then, only with specific lenses. 19 AF points are plenty, but there’s a bigger problem: those 19 AF points are clustered around the center of the frame. The Canon 5D Mark III ($3,300) has 61 autofocus points, and at a glance, would seem to have an inferior autofocus system compared to the a99. However, comparing the autofocus points that can be used for initial focus on a rule-of-thirds grid, as shown in the following figure, tells a different story. The a99’s focus points, on the left, are clustered around the center, requiring you to use the focus-and-recompose technique for every single shot that follows the rule of thirds—and that will be most of your shots. The 5D Mark III’s autofocus points reach much farther, allowing you to autofocus on the left or right third of the frame (but still not all the way to the corners, unfortunately).  The Sony Alpha a99’s autofocus points (left) are clustered around the center of the frame, which is less useful than the Canon 5D Mark III’s autofocus points (right), which are distributed farther across the frame. I don’t mean to criticize the a99 specifically; it’s an amazing camera. I spent the first decade of my photography career only using the center autofocus point (combined with the focus-and-recompose technique), so even just a single autofocus point will get the job done. I’m only showing this example because, as you assess different camera bodies, I want you to put less emphasis on the number of autofocus points and more emphasis on how they’re distributed across the frame.

The Sony Alpha a99’s autofocus points (left) are clustered around the center of the frame, which is less useful than the Canon 5D Mark III’s autofocus points (right), which are distributed farther across the frame. I don’t mean to criticize the a99 specifically; it’s an amazing camera. I spent the first decade of my photography career only using the center autofocus point (combined with the focus-and-recompose technique), so even just a single autofocus point will get the job done. I’m only showing this example because, as you assess different camera bodies, I want you to put less emphasis on the number of autofocus points and more emphasis on how they’re distributed across the frame.

Nikon Focusing Motors

For Nikon camera bodies, there’s one more factor to consider: whether the body has a focusing motor. Whereas most modern lenses have the focusing motor built into the lens, older Nikon lenses relied on a special motor built into the body to adjust the lens focus. Higher-end Nikon DSLRs still include focusing motors to allow autofocus with these older lenses. Specifically, the following recent Nikon DSLRs have a focusing motor: D90, D300, D7100, D600, D610, D800, D810, D3x, D4, and D4S. All other new Nikon DSLRs don’t have a focusing motor. Therefore, autofocus will work fine with all newer AF-S and AF-I lenses, but you won’t be able to autofocus with older AF lenses that require a focusing motor (though you can still use them with manual focus). Fortunately, most of Nikon’s current lineup is AF-S. All you’d really be missing out on is autofocusing with their fisheye lenses, but the wide depth-of-field with fisheye lenses makes focusing easy.

[…] cameras are still reigning when it comes to autofocusing fast moving objects which are very much applicable in sports and shooting wildlife. However, there are certain […]